Alexander III of Macedon (a principality in Northern Aegean), would grow up to become the founder of the world’s first cross-cultural empire in the true sense; an empire spanning 5,200,000 km2, with Greek, Persian, Egyptian, Indian and other subjects would compel history to confer on him the epithet of “ὁ Μέγας ” (ho Mégas/the Great). The breadth of his achievement is nothing short of breathtaking, taking into account both the constrained logistics of transport of the times, as well as the young age at which he died. It can be safely assumed, today, that he was almost perpetually on the march, save for recuperation after a particularly difficult siege. His forces were almost always outnumbered, yet he was defeated only by his own mortality, which finally enveloped him in the grand palace of Nebuchadnezzar II at Babylon (323 BC).

Anyone studying Alexander today would easily perceive the Conqueror as, first and foremost, a brilliant general and a tactician. His exploits, which include the famous battles of Issus (333 BCE), Gaugamela (331 BCE).and notably, Hydaspes (Jhelum) (against Porus)(326BCE) provide avid testimony of the odds he faced and surmounted. It is, perhaps, one of history’s greatest tragedies that he had to bow down to the wishes of his own military and beat a retreat from Beas (Hyphasis); he was never to see his homeland again. What would have occurred had he stayed on is therefore, a matter of some conjecture- a conjecture that is attempted (perhaps, a bit naively) to be addressed here.

For most of his career, Alexander (who set out with barely 45,000 men from Macedon) had to rely on mercenaries. It was perhaps inevitable, in part, to replenish the dwindling numbers of his men succumbing to forced marches, sieges, disease and the like. Some of his men settled in cities that he built, most notably with the name ‘Alexandria’-a name that resonated from Egypt to the Indus.. It was also, perhaps necessary to maintain some local militia experienced in the terrain and adapted to the peculiarities of the climate. It is difficult, and perhaps even ludicrous to believe that the Macedonian Phalanx constituted a majority of his army by the time he fought at Hydaspes. Nearly one hundred years later, Hannibal Barca, the great Carthaginian General would employ such mercenary armies to great effect against an ascending Rome. This would, perhaps also debunk the ‘undisciplined mercenary’ myth, to a certain extent: led by an able leader, a mercenary army might show the same level of cohesion as a regular army. Darius, despite being a good strategist, and deploying superior numbers in the field, was not a soldier, and fled the battle every time he faced Alexander, and his mercenaries in turn, melted away too.It would seem, thus, that the courage of the mercenaries is directly proportional to the courage of those who lead them.

Then why did Alexander turn back? Some historians suggest that the battle with Porus was the most pyrrhic that Alexander ever fought. Others state that his generals and soldiers were weary and wanted to return to their homelands. Only, after his death at Babylon, these ‘Diadochi’ suddenly were at each other’s throats, became busy in carving their own empires within Persia, instead of returning to Macedonia like they so desperately wanted: Ptolemy seized Egypt; Antipater was already in possession of Macedon; Seleucus I Nicator inherited Near East. Something doesn’t add up. It is not my intention to untie thisGordian knot. My only intention here is to set the cat among the pigeons: with luck, it might lead to a new zeitgeist theory leading to further research. My intention here is simply to analyze, with the information the modern world possesses, what would have occurred had Alexander disregarded the opinion of his men and moved on into India. Most of it is at best conjectural, although I shall try my best to supplement it with as many facts as I possibly can. Let us begin.

Historians, such as Plutarch, have vividly described the scene at the banks of Beas, where Alexander made an impassioned speech to his men to march further into the heart of India.

The men, both terrified of what lay in store for them in the heart of India (they had reports of the vast Nanda Kingdom) and tired of continuous wars, ‘mutinied’. While at first sight, it seems entirely plausible, reason would dictate two things: one, the leaders of the mutiny would be the remaining Macedons, who truly came a long way for Alexander’s ambition. Most of the remaining army would be a collection of Persian, Egyptian and other auxiliaries. One of the ways in which the situation could possibly be resolved was to let those Macedonians leave and devolve powers to others who had proven their mettle. Alexander had already acquired two allies in India-Ambhi of Taxila and Porus of Jhelum: it made all the more sense to call upon the vast resources of Persia. Most of the Macedonians were both ambitious and envious of his success (proven later by the treatment they meted out to his wife, Roxana and his mother, Olympia after his death) which would have led to many power foci within his army. It made sense to rid his camp of ambitious Generals by conferring them Satrapies within his extensive empire: later rulers such as Balban used the same method and called it as Iqtadari. As a corollary, for most of the Greeks, Persia was the main enemy: as far as they were concerned, Thermopylae and the sack of Athens had been avenged. Reason permitted letting go of morbid soldiers as well.

The second was, this was not the first time Alexander was outnumbered. Throughout the Achaemenid campaigns, his quarry always seemed to have a numerical advantage. The army of Porus was larger than his own. The same quandary was faced by Babur 1800 years later-he chose to fight and History bestowed on him the title of the First Mughal.

Thus, the scene was set for Alexander’s hypothetical foray into India: the first thing he would have to do is to secure his supply lines from Persia, in case of a contingency. Closer contacts with Persia would mean cultural diffusion as well, and more of Hellenistic and Achaemenid art would have met Indian themes (Read: Asokan pillars would be closer in structure to those of Darius and Xerxes). With Alexander’s advance, the cultural assimilation would inevitably have gained momentum. Depending on the outcome of a conflict with the Nanda King, the Mathura school of Art would be subsumed within the Gandhara school, or not. A larger collection of Gold coins, perhaps converted from ‘gold talents’ would be known to India. The Greeks had mastered the art of coin making earlier than Indians: consequently India would get her first taste of Drachmas, gold and silver Staters (like that of Eucratides, a general of Alexander) from the Hellenestic period, and not from the Kushanas three centuries later, who largely replicated the coins of the Bactrain Greeks. Historical sources also allude to Sandrocottus or Chandragupta Maurya meeting with Alexander, informing him that the Nanda king is ‘vile and hated by his subjects’. The presence of Chanakya is equally probable, since he was a teacher in the Taxila University at that point. However, it is unlikely that Alexander was impressed with either of them, and thus equally unlikely that he would have made Chandragupta a satrap in Magadh. Though he was known to give back small kingdoms back to the rulers once he defeated them, empires were another matter altogether: it was both dangerous and foolhardy. If we assume that Alexander would have been able to defeat Dhana Nanda, the appointment of a successor of a kingdom in the heart of India would have been a real conundrum for him. Perhaps he would have done a Mark Antony and stayed on in a foreign land, however remote the likelihood seemed.

One wonders whether Alexander would, in fact, be able todefeat the mighty Nanda king. Ironically, for this, we need look no further than the Nanda nemesis, Chandragupta Maurya: An exile that succeeded in vanquishing the mighty emperor. It means one of two theories is correct-either the Nanda reputation suffered from megalomania, or the empire had become hopelessly inefficient economically, politically, and militarily. These two reasons, comically, are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Conquering Pataliputra, the ‘Jaldurg’ (bordered by the rivers Ganga, Son, and Punpun) was no joke. The Nanda King was not assassinated by Chandragupta; he fought and was defeated: such defeat smacks of ineptitude. Compare this with the kind of resources Alexander had. It seems like a travesty that he didn’t get the chance.

With no Mauryan empire, the face of ancient India would change beyond recognition. Buddhism would not be what it is today, because Asoka, the grandson of Chandragupta Maurya, would not be the figure he is in ancient India. He would, perhaps be the ruler of some petty principality, too engrossed in the struggle for survival to focus on Dhamma.On the flipside, we would have a multitude of people like Meghasthenes, who, though at times incorrectly, did document the peculiarities of Ancient India. And to imagine the fate of Buddhist countries today! Laos, Cambodia and Sri Lanka would be overtly Hindu, Japan would follow Shinto’s (there would be no Zen), and China would be a blend of Communism and Confucianism. Perhaps, such an assumption is oversimplified, for the absence of Buddhism would trigger different developments in every nation I mention, but I leave it to the enlightened scholars of these countries to disprove me, which they without a doubt should. That is a story for another person, in another time.

Alexander was also known to adopt certain customs of the lands he conquered- a practice that his compatriots disapproved of, but later imitated themselves when they became semi-autonomous Sataraps: the Ptolemies adopted the Pharaoh tradition of sibling marriage, while some later Sataraps took imperial titles like ‘King of Kings’ (Shahenshah). Alexander, while at Persepolis, the Persian capital, embraced the custom of proskynesis: traditional Persian act of bowing or prostrating oneself before a person of higher social rank. He also styled himself as Zeus-Ammon: a joint deity of both Greece and Egypt. It can be safely said that some Indian customs would have intrigued him and like Kanishka, he would have embraced them. These traditions would travel to Europe with soldiers, bards and caravans and fuse into the prevalent fashion of the times.

It is no secret that the last Ptolemy, the famous Cleopatra wanted her only son by Caesar (alleged, but vociferously denied by Roman historians), Caesarion to flee to India after the naval debacle at Actium against Octavius in 30 BC. The Hellenistic empire established there by Alexander would perhaps, have quelled any doubts that Caesarion had about moving to a foreign land, and the dynasty of Cleopatra and Caesar would have survived in India. Interestingly, Caesar had no other children; Octavius was his nephew. Some historians will believe that the lapse of three centuries would have wiped out any traces of Greeks. History does tell us that in the First Century BCE, the Greeks (‘Yavanas’) were still at the northwestern borders of the Saka and Kushana kingdoms. Had Alexander founded an empire in India, the nature of the empire would have been different, with a stronger Greek presence both politically and with more cross-cultural interactions than mere court ambassadors like Meghasthenes. The next paragraph would explain my point.

Finally, a word on the demographics. The Hellenization of North India would bring Greeks deeper into the country than they actually did, because of the way history turned out for them. Marriages to locals would bring them into the Indian fold, and the need for smritiswould have been felt two centuries earlier, just to incorporate the large influx of foreigners into the caste system. It would have changed the North Indian bloodline ever so slightly, adding Aegean ‘aima’ (Greek: ‘blood’) in it. And it would mean that India would record Alexander’s invasion not as a footnote, but as a start of a new order.

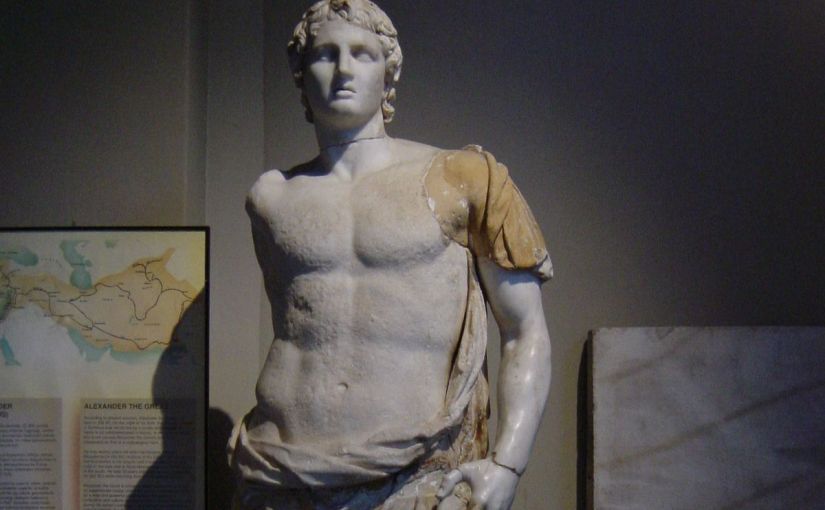

Image sourced from Wikipedia